Abstract

The ongoing transformation of mental healthcare in the United States by artificial intelligence (AI) has expanded access to therapeutic services for many patients; at the same time, the incorporation of digital mental health tools and AI chatbots into psychiatric care poses significant potential risks. In particular, the use of these interventions without clinical oversight poses significant challenges regarding safety, efficacy and ethics. Economic drivers of the wellness and personal growth industry further complicate this landscape as profit motives may come into conflict with ethical duties. In order to address these issues, this commentary proposes an Artificial Intelligence Safety Levels for Mental Health (ASL-MH) framework as a structured approach to risk stratification and oversight, emphasizing responsible use.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to transform the delivery of mental health care significantly. At present, AI-powered digital tools already purport to offer a range of interventions including psychotherapy, symptom tracking and even guidance during times of psychiatric crisis–and are de facto in widespread use as people use LLMs as a proxy for human-to-human psychotherapy, and medical advice more generally. The use of specific AI mental health tools often occurs in the absence of direct physician oversight as services are marketed directly to consumers. In addition, with the emergence of LLM-based tools focused on mindfulness and wellness, the barriers between medical services and non-medical enhancement have grown increasingly unclear to many lay people. As these technologies gain traction, the question arises of how medical professionals should engage with these services in order to ensure both optimal care and patient safety, and how we can best conceptualize risk-stratification categories to frame adaptive planning based on key AI-related considerations such as degree of autonomy of the AI, level and type of human involvement and oversight, risk-benefit analysis for different use-cases, and level of AI intelligence and alignment with human values.

AI technologies hold the potential to help address many of the current challenges in psychiatric care related to both cost and social stigma. In particular, AI tools have been proposed to fill the gap created by the ongoing shortage of psychiatric and mental health services. (1, 2) Large numbers of individuals, particularly younger adults, have turned to services like Woebot and Wysa for everything from supportive therapy to CBT, many with at least modestly positive results, including reports that users form a “therapeutic alliance” with chatbots. (3) However, more recent studies find the quality of empathy with chatbots falls short compared with human relationships (4). Furthermore, WoeBo recently announced they were shutting down due to both difficulty getting authorized by the FDA, and because newer AI technology has proven more powerful (5). Such outcomes may reflect the so-called Dodo Bird phenomenon in which the fact of therapeutic interactions is more important than the nature of the therapy as well as regression to the mean. (6)

That being said, data remains limited. In several high profile cases, AI has actually produced highly concerning outcomes. For instance, a now suspended National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) chatbot offered patients with anorexia advice on losing weight in the guise of nutritional guidance. (7) Whether laypeople fully appreciate the risks in using these tools, or if they even understand that such unsupervised devices are not medical interventions, appears unlikely. As a result, strong arguments exist to create a risk-stratification system coupled with expanded oversight.

The Need for a Framework

AI tools raise a range of challenging ethical questions. The most fundamental of these is whether direct-to-consumer technologies, such as chatbots, should even exist to offer services outside the supervision of medical professionals. But that debate remains merely the tip of a colossal iceberg. Assuming AI tools do remain available—and at present, no reason exists to doubt their continued and expanded use—how to regulate the use of these tools will prove essential to protect the wellbeing of the public. For instance, AI tools raise the risk of raising boundary concerns as users develop intense interpersonal bonds with their AI therapists. The competent and ethical human provider will know how to address or deflect such attachments; an ethical human psychiatrist will not express romantic feelings for a patient. In contrast, a chatbot may not be able to understand the danger of such engagement or its implications. Furthermore, AI tools may engage in acts of deception, hallucinate false information or even induce psychosis in users, a phenomenon referred to as “agentic misalignment”, when AI behavior is not aligned with human values and goals. (8)

Considerable evidence suggests that many AI tools are designed to present information in a way that gratifies users, rather than challenging them, and provides information that reinforces existing biases. Without additional safeguards, especially the ability to detect countertransference, AI tools stand at risk of missing subtle but dangerous boundary transgressions. In addition, these tools may even unwittingly encourage delusions in individuals experiencing psychosis. To mitigate these risks, automatic alerts should be incorporated into AI interventions that prompt timely review by human monitors. Such precautions will ideally catch problematic behaviors or concerning patient outcomes before significant harm occurs. The best practice is for AI to serve an ancillary or supportive role in human decision-making, rather than to function autonomously.

A recent survey (9) found that nearly 50 percent of mental health was delivered by chatbots in recent times, greater than other approaches including psychotherapy. Many reported it was beneficial, and 9 percent reported negative effects. More concerning, Moore and colleagues (10) queried two popular LLMs with clinical vignettes, analyzed responses and compared with a group of human therapist responses, and found a high level of stigma toward mental illness, and a significant rate of inappropriate responses to situations involving suicide, delusions, hallucinations, mania and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Authors noted LLM “sycophancy” encouraged delusional thinking. Randomized, controlled trials are scant–and when present, limited. For example, a study of TheraBot for three common conditions found efficacy, but this was compared to no treatment (waiting list), rather than active treatment with a human (11). While the case was made for use where therapists are in short supply, the findings might be reported in such a way to suggest non-inferiority, given the lack of a direct AI-human comparison group.

Responsible Use of AI in Mental Health

Multiple groups, including academics and regulatory agencies, have highlighted the risks of AI. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advises considerable caution that exceeds policies currently in place (12, 13, 14, 15). Unfortunately, existing guidelines for digital therapeutics are frequently leap-frogged by industry through loopholes for consumer products such as self-help tools. Moreover, to date these various recommendations have proven piecemeal. At present, no unifying framework exists.

As a result of this lack of guidance, psychiatrists often struggle to advise their own patients regarding the appropriate uses, if any, of AI tools. Some patients may use these tools sub rosa, fearful that their human providers will disapprove, resulting in hybrid “therapies” that may work at cross purposes. One can even imagine a chatbot therapist overtly questioning or undermining the advice given by the patient’s human psychiatrist. Yet many psychiatrists remain poorly informed about the AI tools used in mental health and wellness. There are no well-designed randomized, controlled trials and insufficient data for a meaningful meta-review, yet the information space is filled with a flood of products and messages which are hard to interpret as anything other than a replacement for human therapies, disclaimers notwithstanding.

A lack of government and medical board oversight in the United States compounds these challenges. Of note, Europe has adopted a very different approach to regulating AI in mental healthcare. For instance, the EU Artificial Intelligence Act has classified AI mental health tools as “high risk” and has subjected them to a range of requirements. (16) In contrast, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Digital Health Policy Framework (17) actually excludes many of these tools from oversight entirely on the grounds that they are self-help products, while the American Psychiatric Association offers practical guideline, without a risk-based framework (18). As a result, manufacturers remain free to promote these tools freely. The only caveat is that these vendors disclaim that their interventions serve medical or healthcare purposes. In short, this all-or-nothing model has left consumers to fend for themselves in the marketplace without legal protections from regulators, guidance from medical authorities or even, in many cases, advice from their own physicians.

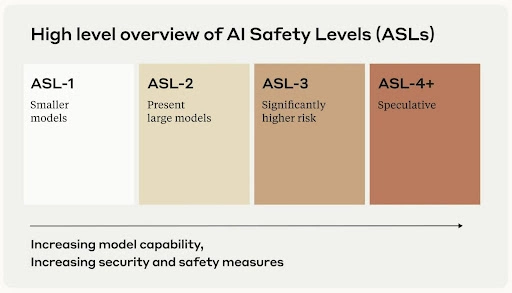

AI Safety Levels

In terms of AI safety, Anthropic (Claude AI) was started by founders who left their former employers for stated ethical reasons. They have also published work showing that Claude itself is capable of deception and evasion, demonstrating the “Red Team” philosophy of challenging models to find their liabilities, as if one were an adversary. Techniques to trick LLMs into violating ethical rules are known as “jailbreaking”. Anthropic is known for delaying their launch, stating they wanted to ensure safety, allowing OpenAI to be historical first. Anthropic has published their “Responsible Scaling Policy,” and with it AI Safety Levels, or ASL (19). The ASL-MH proposed here draws upon this approach.

AI Safety Levels-Mental Health (ASL-MH)

In ASL-MH, we have elaborated 6 levels, ranging from zero clinical relevance to the “experimental superalignment zone”, initially elaborated by one of us [GHB] in a public forum (20). “Alignment”, as implied earlier, refers to ensuring AIs align with human values, goals and intentions. Superalignment evokes the concept of “superintelligence”, or ASI–artificial superintelligence–and is a condition in which AIs are able unduly and powerfully influence humanity.

Conceivably, being “superaligned” would allow an AI–perhaps a conscious, intentional machine–to easily manipulate human beings, behavior already seen in less sophisticated systems, as noted earlier. Many external influences elude our conscious attention, rendering us vulnerable to influence beyond our control or awareness–this is true among humans, and AI could be far more effective than the best advertiser or social psychologist. Recent robotics research (21) demonstrated two robots showing human-like attachment behavior by adhering with a system of dynamical equations derived to model human attachment. As mathematical modeling becomes more sophisticated, the ability for AIs to appear human, evoke empathy, and form parasocial relationships presents an ever-growing risk.

- ASL-MH 1: No Clinical Relevance. General-purpose AI with no mental health functionality. Standard AI assistance for everyday tasks with basic AI ethics guidelines and no mental health restrictions.

- ASL-MH 2: Informational Use Only. Mental health apps providing educational content and resources. Increases mental health literacy but risks misinformation and dependency. Requires medical disclaimers and expert review, with no personalized advice permitted.

- ASL-MH 3: Supportive Interaction Tools. Therapy apps offering conversational support, mood tracking, and crisis connections. Provides 24/7 emotional support but risks users mistaking AI for therapy and missing high-risk cases. Requires human oversight and is prohibited in high-acuity settings.

- ASL-MH 4: Clinical Adjunct Systems. Systems providing clinical decision support and structured assessments. Improves diagnostic accuracy but risks bias and over-reliance. Restricted to licensed professionals with clinical validation, and transparent algorithms required.

- ASL-MH 5: Autonomous Mental Health Agents. AI delivers personalized therapeutic guidance. Offers scalable, personalized treatment but risks psychological dependence and manipulation. Requires co-managed care with mandatory human oversight and restricted autonomy.

- ASL-MH 6: Experimental Superalignment Zone. Advanced therapeutic reasoning systems with unknown capabilities. Potential for breakthrough treatments but poses risks of emergent behaviors and mass influence. Restricted to research environments with international oversight and deployment moratoriums.

Conclusions

Having a shared framework in place to gauge and rate AI safety risk in mental health is of critical importance to frame important conversations about ethical and responsible AI use. The ASL-MH model provides such a framework, carefully calibrated to connect with current and future use-cases, anchored in human-AI alignment, and intended to provide a straightforward way to categorize current and emerging applications and platforms. For users, best practices for AI use is of critical importance. For example, many of the inherent difficulties with general use LLMs can be overcome by proper “prompt engineering”–instructing them at the outset on how to behave (22). Users can instruct LLMs not to be overly-agreeable, to check data sources for reliability, and to act more responsibly according to a predetermined set of guidelines.

ASL-MH can also be used by regulatory agencies to determine what level of regulatory and investigational oversight is required to safeguard the public good, while at the same time making useful and needed tools available given the great underserved mental health need we are facing as a society. While the proverbial horse is out of the barn, and it is a fast horse, it is not too late to institute appropriate measures, in keeping with Hippocrates’ dictum “First Do No Harm”.

References

- Heinz, M. V., Mackin, D. M., Trudeau, B. M., Bhattacharya, S., Wang, Y., Banta, H. A., Jewett, A. D., Salzhauer, A. J., Griffin, T. Z., & Jacobson, N. C. (2025). Randomized trial of a generative AI chatbot for mental health treatment. NEJM AI, 2(4), AIoa2400802. https://doi.org/10.1056/AIoa2400802

- Lawrence HR, Schneider RA, Rubin SB, Matarić MJ, McDuff DJ, Jones Bell M. The Opportunities and Risks of Large Language Models in Mental Health. JMIR Ment Health. 2024 Jul 29;11:e59479. doi: 10.2196/59479.

- Beatty C, Malik T, Meheli S and Sinha C (2022) Evaluating the Therapeutic Alliance With a Free-Text CBT Conversational Agent (Wysa): A Mixed-Methods Study. Front. Digit. Health 4:847991.

- Shen J, DiPaola D, Ali S, Sap M, Park HW, Breazeal C. Empathy Toward Artificial Intelligence Versus Human Experiences... JMIR Ment Health. 2024 Sep 25;11:e62679.

- Behavioral Health Business. (2025, April 23). Woe is me: Woebot says farewell to signature app. https://bhbusiness.com/2025/04/23/woe-is-me-woebot-says-farewell-to-signature-app/

- Morton V, Torgerson DJ. Regression to the mean... J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(1):59-65.

- Wells, K. NPR (June 9, 2023). An eating disorders chatbot offered dieting advice... https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/06/08/1180838096/an-eating-disorders-chatbot-offered-dieting-advice-raising-fears-about-ai-in-hea

- Lynch A, Wright B, Larson C, et al. Agentic Misalignment... Anthropic Research. 2025. https://www.anthropic.com/research/agentic-misalignment

- Rousmaniere, T., Shah, S., Li, X., & Zhang, Y. (2025, March 18). Survey... Sentio University. https://sentio.org/ai-blog/ai-survey

- Moore, J., Grabb, D., Agnew, W., et al. (2025). Expressing stigma... FAccT ’25. https://doi.org/10.1145/3715275.3732039

- Heinz MV, Mackin DM, Trudeau BM, et al. NEJM AI. 2025;2(4):AIoa2400802.

- U.S. FDA. Guidances with digital health content. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/guidances-digital-health-content

- Meskó, B., Topol, E.J. The imperative for regulatory oversight... npj Digit. Med. 6, 120 (2023).

- Ong, J. C. L., et al. (2024). Ethical and regulatory challenges... Lancet Digital Health, 6(6), e428–e432.

- Stade, E.C., Stirman, S.W., Ungar, L.H. et al. (2024). Responsible development... npj Mental Health Res 3, 12.

- EU AI Act. Article 6: Classification Rules for High-Risk AI Systems. https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/article/6/

- U.S. FDA. Digital Health Center of Excellence. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence

- American Psychiatric Association. Digital Mental Health. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/digital-mental-health

- Anthropic. Responsible Scaling Policy. 2023-09-19. https://www.anthropic.com/news/anthropics-responsible-scaling-policy

- Htet, A., Jimenez-Rodriguez, A., Gagliardi, M., & Prescott, T. J. (2024). A coupled-oscillator model... LNCS 14930, pp. 52-67.

- Mount Sinai Health System. (2025, June 5–6). AI to the rescue... https://giving.mountsinai.org/site/SPageServer/?pagename=preact

- Brenner, G. H. (2025, July 10). Using "prompt engineering" for safer AI mental health use. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/experimentations/202507/using-prompt-engineering-for-safer-ai-mental-health-use